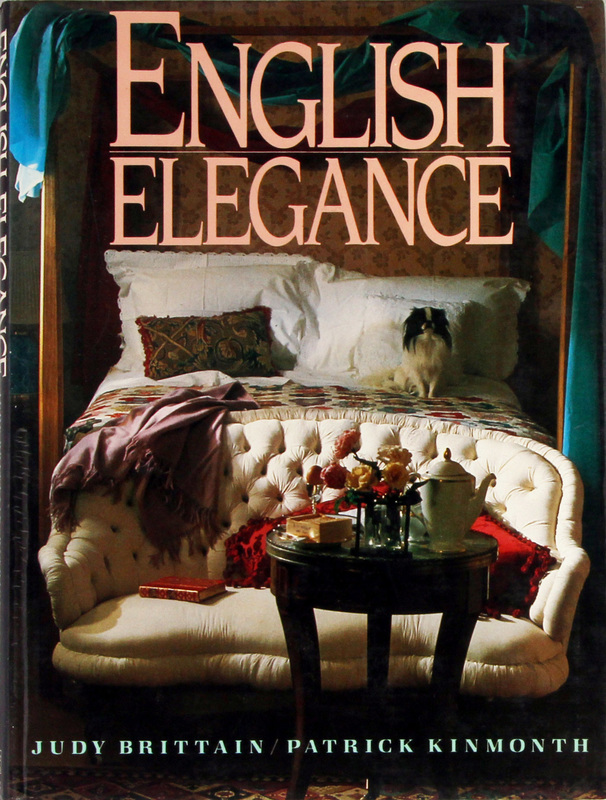

“Your aunt Joanna has let herself go,” Barty said. “I saw her at the Devonshires’ the other night. She sat down and her bottom spread over the sofa like a ripe Brie.”

“Poor Aunty Jo,” Emeline said with feeling. “She never got over losing Topper.”

“I thought her husband was called Charles?”

“He was—Topper was her Pekinese.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed