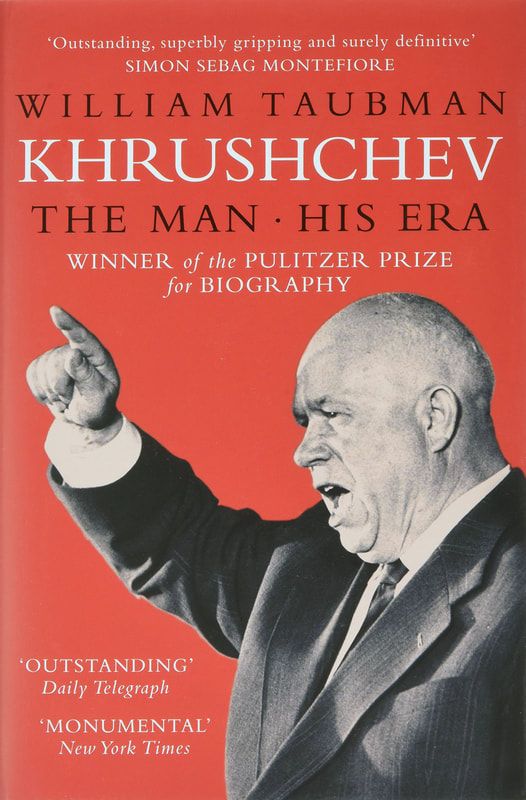

Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev, The Man and His Era

It is impossible to put a positive spin on the bad. Khrushchev was a faithful henchman to brutal Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. It explains his improbable rise from peasant stock to Politburo heavyweight. Working under Stalin was akin to playing Russian Roulette. It was a game of chance that could easily result in death. Had morality gotten in Khrushchev’s way, it would have ended his career and probably his life. Yet, Khrushchev was not simply following orders to survive. Richard Pipes, writing for the New York Times, concluded, “While most of his minions feared and detested Stalin, Khrushchev actually came to admire him. Having become in the 1930's Stalin's pet, he enthusiastically participated in his slaughters.”

Furthermore, Khrushchev’s ruthlessness did not end with Stalin’s death in 1953. In his defense, it couldn’t. There was no definitive line of succession built into the Soviet political structure, and only by manipulation did Khrushchev become leader. His actions were not exactly as they were portrayed in the recent black comedy The Death of Stalin, but nor could they be categorized as nonviolent.

It was after Khrushchev firmly established his hold on power (circa 1956) that he took Kremlin watchers by surprise by publicly denouncing Stalin and reversing the worst atrocities of his regime. Fearing annihilation in an un-winnable nuclear war, Khrushchev also initiated détente with the West. It turned out that he did have a conscience (or somehow acquired one). From the hindsight of the 21st Century, we now understand that Khrushchev's historical significance is more as a precursor to Mikhail Gorbachev than as barbaric protégé to Joseph Stalin.

As part of his détente initiative, Premier Khrushchev embarked on a state visit to the United Kingdom. He was not a worldly man. Knowing only the barbarousness of home, he could did not quite understand the non-violent nature of a Western-style democracy. When Khrushchev’s interpreter fell ill, a mistake in translation illustrated that point quite brilliantly.

The hastily acquired substitute interpreter, whose ruddy complexion suggested he had been drinking, was not up to the task. When avid outdoorsman Lord Tony Lambton was introduced to Khrushchev as being the best shot in England, the interpreter clumsily translated it into Russian as, “Lord Lambton is to be shot tomorrow.” This was absurd. Execution without trial did not happen in 20th Century Great Britain. Yet, Khrushchev, accustomed to life in the Soviet Union, was oblivious. He took it to mean that Lord Lambton "was under sentence of death, and shortly to be executed." Per Lady Diana Mosley (who heard the story directly from Lord Lambton), "Khrushchev thought it quite normal but patted him on the shoulder kindly."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed