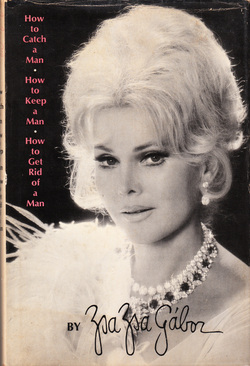

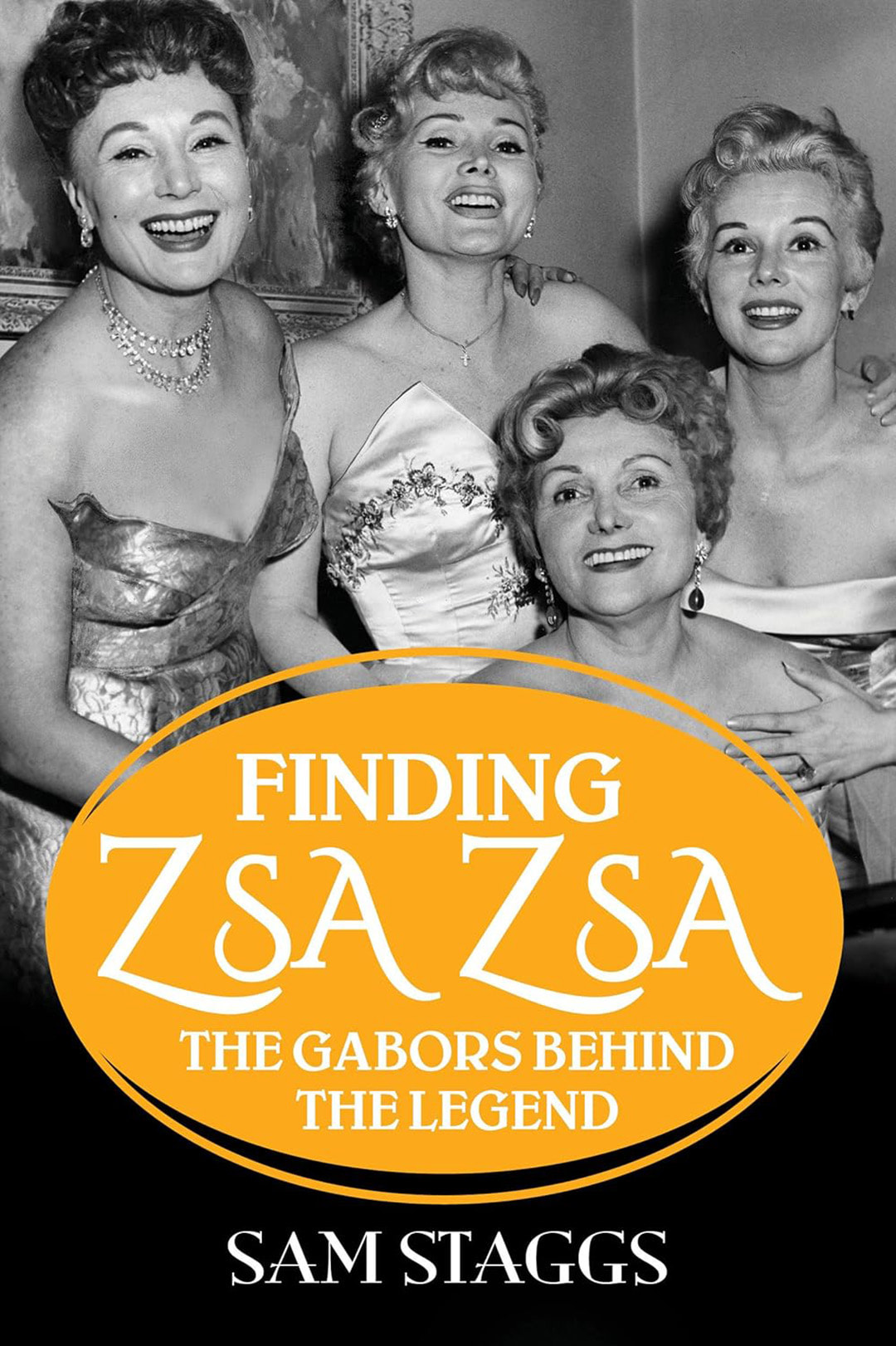

Zsa Zsa Gabor, Finding Zsa Zsa: The Gabors Behind the Legend

|

“If one has a cross to bear, it might as well be diamonds.”

Zsa Zsa Gabor, Finding Zsa Zsa: The Gabors Behind the Legend

0 Comments

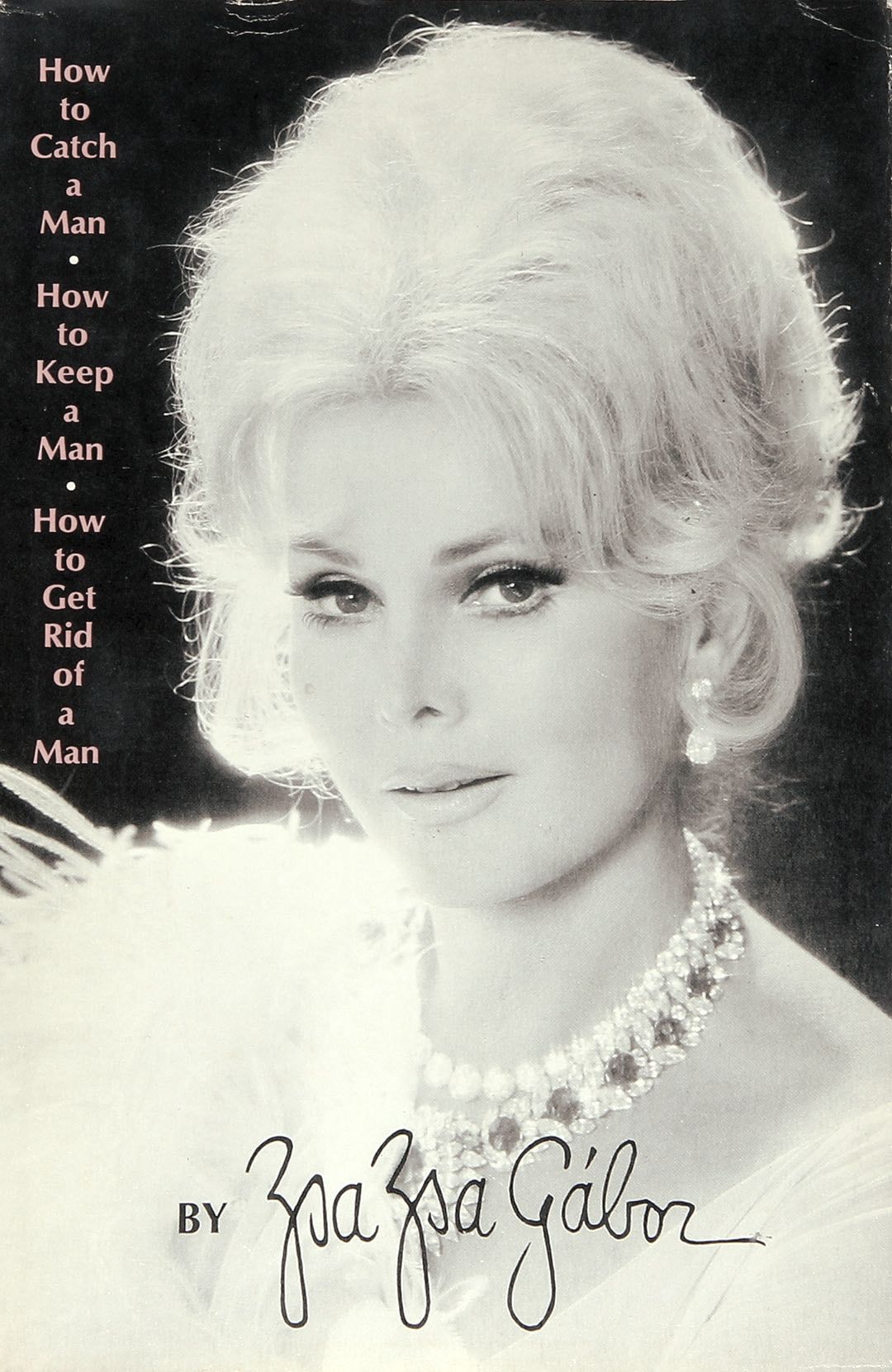

“[A] problem you’ll have when you read my advice is that you may get mixed up, because it is not always logical and consistent. Don’t worry, though. Advice that’s not logical and not consistent is the very best kind.”

Zsa Zsa Gabor, How to Catch a Man “How many husbands have I had? You mean apart from my own?” Zsa Zsa Gabor, One Lifetime Is Not Enough Image Credit: Oscar Night, From the Editors of Vanity Fair

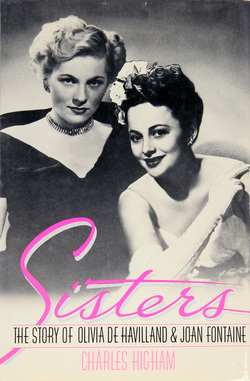

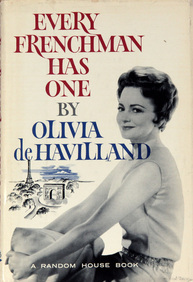

"On television and in night club shows when a girl asks me, 'If the engagement is broken, do I have to give back the ring?' I answer, 'By all means! Give back the ring but keep the stone.'" Zsa Zsa Gabor, How to Catch a Man Sisters, The Story of Olivia de Havilland & Joan Fontaine by Charles Higham. NY: Coward-McCann. 1984. Available for purchase at Nick Harvill Libraries, here. REVIEW OF THE BOOK  "Sisters" by Charles Higham "Sisters" by Charles Higham “My sister has decided to become an actress too. It has ruined the close-knittedness of our family life.” Olivia de Havilland “What a pity [Olivia’s new husband] has had four wives and written only one book.” Joan Fontaine “It is unlikely that Joan and Olivia will ever talk to each other again; when both turned up at the fiftieth anniversary of the Academy Awards in 1979, they had to be placed at opposite ends of the stage; and when they ran into each other in the corridor of the Beverly Hills Hotel, they marched past each other without a word.” Charles Higham Charles Higham, once the Hollywood correspondent for the New York Times, was a prolific biographer of film stars from Hollywood’s Golden Age. Unfortunately for his subjects but fortunately for the rest of us, the word “hagiography” was not in his vocabulary. He dove into controversy headfirst. Moreover, he was intrigued by psychological disturbances, tackling personalities that might have benefited from Freud’s couch. He wrote about the Nazi sympathies of Errol Flynn, the bisexuality of Cary Grant, and the peculiarity of Howard Hughes (the 2004 Hughes biopic The Aviator was based upon one of his books). Here, he takes on the unprecedented ninety-year feud between Oscar-winning sisters Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine, whose rivalry began when both were toddlers and continued until 2013, when Joan died at the age of ninety-six. Like any decent Freudian, Higham mines the childhood of the sisters, which was as gothic as anything Joan Fontaine’s erstwhile director Alfred Hitchcock might have devised. Of noble British origins, the girls’ father Walter was living in Japan when they were born, but their sharp-tongued mother Lillian fled with them to California, landing in a San Jose, California boarding house. Lillian almost always sided with angelic Olivia, leaving acerbic Joan to lobby for attention through tantrums and imagined illnesses. Fed up, a teenage Joan fled to live with her father in Japan but returned in horror when he made sexual advances towards her. That ignoble scene would come back to haunt both sisters when they were famous, and Walter had the audacity to blackmail their studios with an autobiographical screenplay he wrote suggesting incest. One of the great stories Higham covers is Olivia de Havilland’s thrilling Hollywood debut in 1934. It is an extraordinary tale—far more dramatic than Lana Turner’s alleged discovery at Schwab's Drugstore. How curious that it has not found its way into the upper echelon of Hollywood lore. It began with Olivia’s participation in high school production based upon Max Reinhardt’s interpretation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Improbably, Reinhardt was in Berkeley, California at the time, and his key people made the trek to San Jose to see the show. They were impressed by Olivia’s performance, so much so that she was invited to observe the lavish Reinhardt production of it that was to be staged at the Hollywood Bowl. Upon arriving in Hollywood, seventeen-year-old Olivia managed to finagle her way into becoming the understudy to the understudy for the part of Hermia, the part to be played by Gloria Stuart. However, both Stuart and her understudy were called up by their film studios just days before the opening, leaving Reinhardt no choice but to substitute Olivia. It was the most extravagant production ever mounted in Los Angeles, and the Hollywood Bowl was renovated to resemble an enchanted forest, complete with live oak, elm, and aspen trees. Joan Crawford, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Norma Shearer, and Louis B. Mayer were among the 20,000 attendees captivated by Olivia’s performance. De Havilland became a star and was signed by Warner Brothers. Gloria Stuart, for whom Olivia subbed) would have to wait another sixty years for her ship (James Cameron’s Titanic) to come in. About this time, Joan returned from her disastrous attempt to live in Japan with her father. She moved to Hollywood, announcing her intention to also become an actress. Neither Lillian nor Olivia supported her in this, and she was permitted to do so only by changing her last name to Fontaine, the surname of her stepfather. The director George Cukor was one of her early supporters, and he gave Joan her big break by casting her in The Women. There are long periods in the sister’s lives when they were not speaking, but even so, their lives ran oddly parallel, which Higham deftly portrays. One such occasion was when George Cukor invited Joan to audition for Gone with the Wind. Fontaine, like every other actress in Hollywood, wanted to portray Scarlett O’Hara. With her willful personality, it might have proved a good fit, but Cukor would not hear of it, thinking of her instead for the role of the kindly Melanie Hamilton. Turning down the part, Joan suggested, “Melanie! If it is Melanie you want, call Olivia!” Which, Cukor did. Olivia became a lifelong friend with her GWTW co-star Ann Rutherford, who played one of Scarlett’s sisters. Years later, in one of those odd examples in which Olivia and Joan’s lives tended to intertwine, Rutherford would marry Joan’s ex-husband William Dozier, becoming the stepmother of Joan’s daughter Deborah.  Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine Olivia de Havilland and Joan Fontaine As Higham writes, there was much kindling for the sister’s feud, and their mother Lillian usually made things worse. After Olivia turned down her paramour Howard Hughes’s ridiculous proposal that they marry but only after a multi-decade engagement, Joan responded to Hughes’s advances, and he made the same proposal to her. It appeared that Joan might overtake Olivia entirely. She was the first to wed, win an Oscar (in a year in which Olivia was also nominated), and have a child. In regard to Joan's pregnancy announcement, their mother Lillian did nothing to lessen the tensions. She caustically replied, “Now you can put the child on the mantelshelf along with your Oscar!” Lillian had an equally acerbic answer to gossip columnist Louella Parsons's suggestion that Lillian must be proud to have two such talented daughters, quipping “Joan may be a phony in life, but she’s almost believable on the screen." Higham covers their six marriages (four for Joan, two for Olivia), de Havilland's landmark case against Warner Brother’s that mortally wounded the studio system, the famous 1961 Bel Air fire that destroyed Joan’s home, and a rogues' gallery of scandalous love affairs (Olivia with Errol Flynn and John Huston, and Joan with Prince Aly Khan, Slim Aarons, and numerous others). There were, however, occasional détentes between the sisters. At the twilight of their careers, long after Olivia had moved to Paris, financially shrewd Joan even came to cash-strapped Olivia’s rescue by writing her a large check. Though Olivia does not exactly come off as Melanie Wilkes to her sister's Scarlett O'Hara, of the two sisters, she was the better mother. In fact, Fontaine's parenting technique causes one to wonder whether the wrong Joan was declared "Mommie Dearest." Fontaine cut off all contact with her daughter Debra, not even bothering to respond to an invitation to Deborah’s wedding. That, however, is nothing compared to her treatment of Martita, the waif she adopted from Peru as a toddler and then abandoned. Things went smoothly for a while, but when a teenage Martita irked Joan, she attempted to have the frightened girl deported back to Peru. Even Joan Crawford would not have dared. This story stops in 1984 when the book was published. One presumes it will not be the last word on one of Hollywood’s great feuds. The available evidence indicates the sisters did not speak after their mother's funeral in 1974, but with Joan dead and Olivia nearing one hundred, additional sources might be willing to go on the record. Even if another book eventually emerges, this volume has much to offer. It is an excellent psychological assessment of the sisters and the peculiar family from which they emerged. EXCERPTS FROM THE BOOK ON THE SISTERS AS YOUNG GIRLS. The opinion of Hazel Bargas who owned the boarding house where the sisters were raised: “It was Olivia who was so sweet, so kind . . . full of life and laughter. . . But Joan! We all hated her. She would always be sick on purpose and she would lie in bed all day and she wasn’t really sick at all, she was just hungry for attention.” AUTHOR’S INTERACTION WITH THE SISTERS. “Meeting the de Havilland sisters—Olivia in 1965, Joan in 1977—was very instructive. Olivia, dignified, matronly, proper, correct, yet sentimental and romantic underneath, was the opposite of Joan, who was relaxed, supersophisticated, brittle, unromantic, and pagan.” OLIVIA WAS NO MELANIE WILKES. “Olivia flatly refused to learn to sew; every time [her stepfather] or [mother] forced [her to], she would instantly prick her finger with the needle and scream very loudly at the sight of blood. When asked to wash the dishes, she would quietly let one slip through her fingers with the words ‘It has a will of its own.’ When Olivia passed her hand-me-downs on to Joan, Olivia always made deliberate tears in them so that Joan would have to sew them.” OLIVIA’S LANDMARK LAWSUIT AGAINST WARNER BROTHERS. “There is no question that the great power today of the stars and their agent and the collapse of the old studio system is in part due to her action.” A STREETCAR NAMED DE HAVILLAND. “Olivia was offered the part of Blanche opposite Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire, and Joan was offered the part of the ‘other sister’—a fantastic concept of Charles Feldman, the famous agent turned producer of the film. Both stars were actually seriously considering the possibility, but fortunately this horrible idea fell through and Vivien Leigh and Kim Hunter were chosen instead.” MARRIAGE. “Certainly, it’s easy to see that Joan was totally incapable of the shifts of ground, the self-sacrifices, adjustments, and considerations necessary in any marriage. Like Olivia, she was far too strong to be married; her will completely quashed all in her path and eliminated any chance she might have had at personal happiness.” PSYCHOLOGICAL REASON FOR THE FEUD. “Above all, the sisters disliked each other not so much because of their differences as because of their similarities. Few actresses admire themselves; they become actresses to conceal their true identities and overcome their insecurities. That is why they need constant flattery and reassurance. The de Havilland girls, however, could not escape themselves, because each could see herself in the mirror of the other.” HAPPY, AT LAST. “Olivia has always wanted to be surrounded by love and attention; to command; to be the focus. Joan has always wanted to be totally free. So the sisters have achieved, each in her way, a purpose in their extraordinary lives—at last.” EPILOGUE/FURTHER READING OLIVIA DE HAVILLAND MEMOIRS. As Higham noted in his book, Olivia signed a deal to write her memoirs in the 1970s, but she abandoned them. In recent years, she reconsidered. However, the journalist Eve Gordon reports that de Havilland gave up, because “her eyes cannot stand computer-screen glare anymore.” In that same story, Olivia offers her own judgment on this book (it is not favorable). Gordon warned de Havilland that if she doesn’t write her own memoir, “others will write horrible lies about her.” Olivia replied, “They already have—have you read that dreadful Charles Higham?” For a full account of Eve Gordon’s May 2012 visit with de Havilland at her Paris home, go here.

ALFRED HITCHCOCK. Joan Fontaine won an Academy Award for her role in Suspicion. She was the only actor ever to win an Oscar for a performance in an Alfred Hitchcock production. Though Higham does not mention it, Fontaine’s acting in her first Hitchcock film, Rebecca, was considered weak and required significant doctoring during post-production. See Spellbound by Beauty, Alfred Hitchcock and His Leading Ladies by Donald Spoto, which is available in a set of books about Alfred Hitchcock, here.

DEATH OF JOAN FONTAINE. Fontaine died on December 15, 2013 at her home in Carmel. Her sister Olivia issued this statement: "I was shocked and saddened to learn of the passing of my sister, Joan Fontaine, and my niece, Deborah, and I appreciate the many kind expressions of sympathy that we have received." For Fontaine’s New York Times obituary, go here. CHARLES HIGHAM. Charles Higham continued to write Hollywood biographies upon completion of this book in 1984. He died in 2012. His obituary in the Los Angeles Times is available here. postscriptSince this post was published in 2014, Vanity Fair profiled the feuding sisters, with some tantalizing clues about what happened between them in the years after 1984, the year Charles Higham's book was published. For NHL's summary, go here.

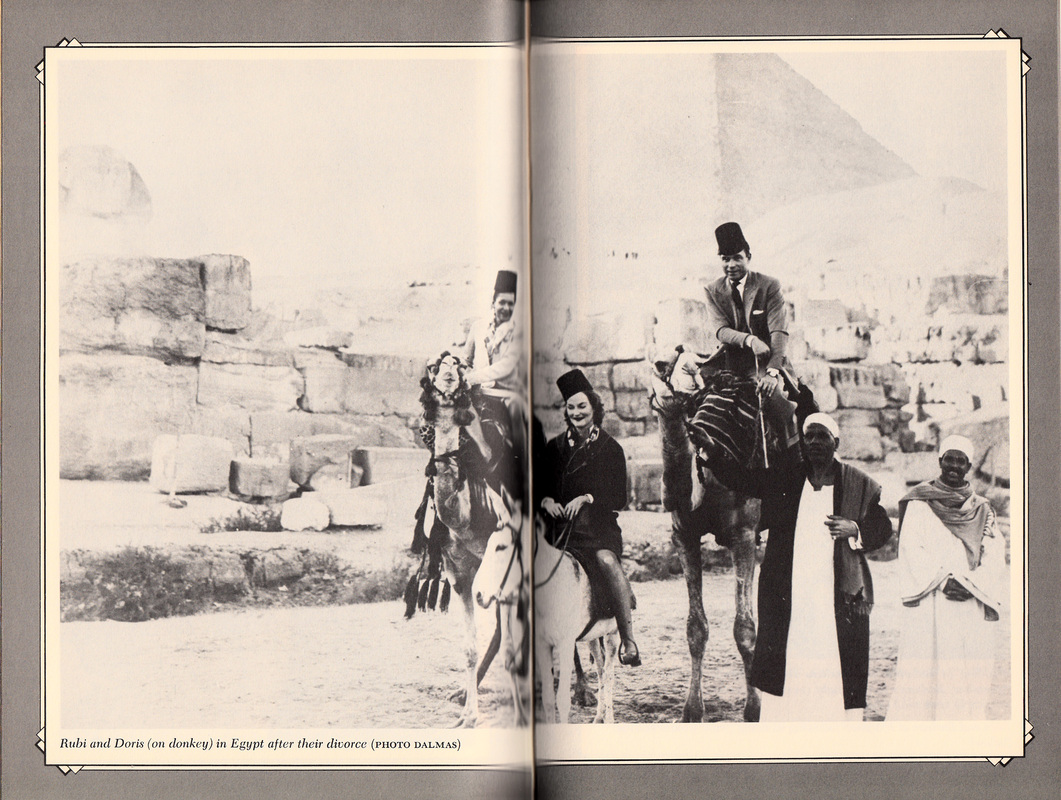

The Million Dollar Studs by Alice-Leone Moats. NY: Delacorte Press. 1977. Available for purchase at Nick Harvill Libraries, here. review of the book “The highest stud fee paid to date for a service by a thoroughbred stallion is $100,000. That may not be hay, but it is when compared to the sums collected by human studs from rich wives.” Alice-Leone Moats “Those who are rich by inheritance tend to be unimaginative about spending money.” Alice-Leone Moats “I am the same as thousands of other men who have fallen in love and married. But I’m a monstrosity. Why? Because I have made the mistake of loving and marrying heiresses.” Porfirio Rubirosa In the heady days of café society, there was a subset that in hindsight might now be called “Viagra society”—the lust and wealth-driven men who bedded and wedded the wealthy heiresses of the mid-20th Century. We are fortunate that Alice-Leone Moats was there to record their exploits in The Million Dollar Studs. Moats was born into old society but loved intrigue so much that she interacted with the nouveaux riche café society types, and she writes about them here as friends and social acquaintances. She even finds herself a supporting player in the drama, offering advice to Barbara Hutton’s father, overhearing conversations in powder rooms, and attending the debutante balls that placed wealthy heiresses on the marriage market. The story of The Million Dollar Studs begins with the Russian Revolution, when the Mdivani family fled Georgia with their lives but not their fortune. Not to worry, somewhere along their perilous journey to Paris, they acquired a phony royal title, which they would use to great advantage in their quest to replenish the family coffers. There were five Mdivani siblings: three brothers and two sisters. One of the sisters, Roussie, proved as conniving as her brothers. She stole Jose Maria Sert from her mentor Misia Sert. However, it is the male siblings who became known as the “Marrying Mdivanis” that are profiled here. Among their conquests were leading actresses of the silent film era, whom they bankrupted, and heiresses like Barbara Hutton, Louise van Alen, and Virginia Sinclair. If there is a heroine in this sordid tale, it is Louise van Alen, a young heiress related to Astors and Vanderbilts. She married two of the Mdivani brothers and somehow lived to tell the tale. Against the better judgment of her family, she first wed the most handsome of the three, Prince Alexis. He divorced her to marry Barbara Hutton, becoming the first in Hutton's rogues' gallery of husbands. Barbara soon divorced him, leaving him with a generous settlement that was disbursed among the surviving Mdivanis when he died in a 1935 car crash. Around this time, Louise married Prince Serge Mdivani, the least handsome, particularly in his later years. In some photographs, he is so rotund he resembles Elsa Maxwell. Prince Serge must have had charm, however, because Louise was disconsolate when he died after falling from his polo pony. Serge was terrible with money, but his estate contained a legacy from deceased brother Alexis. Half of that went to Louise upon Serge’s death. In this roundabout manner, Louise saw some of divorce settlement to Alexis returned to her, as well as the small fortune that had been settled upon him by her romantic rival Barbara Hutton. As result of Serge's death, Louise became the sole woman to actually make a profit from marriage to a million dollar stud. In estate negotiations with the surviving Mdivani siblings, she relinquished Serge’s share in real estate worth $4,000 in exchange for shares in the Naphtha Oil Company. Naphtha soon struck oil, adding $6 million to Louise’s already substantial portfolio. The second half of the book concerns legendary lover Porfirio Rubirosa who had something much grander than a phony title to offer his heiresses. In spite of Moats’ proper upbringing, she is not above investigating why he was so valued as a lover, interviewing his conquests about his size, tumescence, and stamina. She even quizzed Jerome Zerbe on his famous statement that Rubirosa’s equipment resembled “Yul Brynner in a black turtleneck.” Rubirosa married his way into the Dominican Republic diplomatic corps, offering much more than merely his credentials. Stranded in France during World War II, he didn’t let occupation by the Nazis interfere with his hedonistic lifestyle. As Moats writes, even during wartime, “his only suffering was due to his old nemesis, ennui.” Ultimately, Porfirio married both Doris Duke and Barbara Hutton and carried on an affair with Zsa Zsa Gabor that enthralled the gossip columnists for several years, reaching its apogee when he allegedly gave her a black eye. Alice-Leone Moats does a masterful job of telling the story. Her tone is more cheeky than moralizing. However, given the foolishness of the heiresses and the fecklessness of the Mdivanis, she cannot help but occasionally inject moral reproach into the tale. In fact, at the book’s conclusion, she points out that the studs frequently died as result of toys given to them by their benefactors (Alexis Mdivani and Rubirosa in crashes of their sports cars and Serge Mdivani on his polo pony). FROM THE BOOKON THE "MARRYING MDIVANIS." “The background the Mdivanis invented for themselves had the defect of being terribly hackneyed. Right after the Russian Revolution, exiled princes who had lost immense estates, splendid palaces, and fabulous jewels were a dime a dozen; the phonies were a penny a hundred. The true story of the Mdivanis is a much better story.” ON PRINCESS ROUSSIE MDIVANI. “Long before the existence of hippies, she dressed in hippie style, but a very elegant Chanel version of it—boots, shiny raincoats, boleros embroidered with colored stones, beanies tuck on the back of her head.” THE AUTHOR’S UNHEEDED ADVICE TO BARBARA HUTTON’S FATHER. “I recall an argument I had with Frank Hutton just before [Barbara’s] eighteenth birthday. He boasted of having succeed in keeping his daughter in the dark as to her wealth, at which I said, ‘That was criminal. She should have been brought up aware of it and of the duties it would entail.’” CAFÉ SOCIETY VERSUS THE DECAFFEINATED KIND. “At that time, New York society still existed and was still stratified. The descendants of the early settlers formed the top layer, but they were so conservative, thrifty, reclusive, and exclusive that their activities were too colorless to be worth recording and their names didn’t appear in the papers except as members of charity committees. Next came the descendants of the more swinging members of the Four Hundred, most of whom had country houses on Long Island’s North Shore. When they went to Palm Beach or some other resort, they mingled with the third layer—café society—as well as the Donahues, Huttons, Kennedys and other nouveaux riches, but they treated them like shipboard acquaintances, dropping them when they got back to New York.” BARBARA HUTTON’S DEBUT IN SOCIETY. “Nothing that Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer produced on the screen in the way of a background for millionaires at play could compare to this ball. It was also one of the best debutante parties ever given. Most of us stayed for a breakfast of scrambled eggs and sausages at eight in the morning.” A FORMER LOVER’S PRAISE FOR PORFIRIO RUBIROSA’S “CHARM.” “It was never hard and never soft. This permitted him to go on and on and on. It was the secret of his charm. I’ve never known anybody who could last that long.” ON DORIS DUKE. “The daughter of tobacco magnate James B. Duke, with a tax-free income of close to $4 million a year, was to a collector of wealthy women what a Titian would have been to J.P. Morgan.” EPILOGUE/FURTHER READINGPRINCE DAVID MDIVANI. Prince David was the only brother to see middle age, dying in 1984 at the age of eighty-four. He is also the only brother to have produced offspring. One of his two sons worked for the Malibu sheriff’s department for many years, before he ran afoul of the law and lead police on a thirty-mile care chase. David’s first wife, the actress Mae Murray, became homeless, living on the streets of St. Louis before being admitted into the Motion Picture Retirement Home. Read more about David Mdivani.

LOUISE VAN ALEN. Louise remarried and spent the rest of her life out of the spotlight, dividing her time between an estate in Santa Barbara and an apartment in Paris. Read more about Louise Van Alen. HONEY BERLIN. One of the heiresses Prince David attempted to marry was Honey Johnson. He spirited her away from New York to Venice, but her parents successfully intervened. She then wed Richard E. Berlin, longtime president of the Hearst Corporation. Among their four children was Andy Warhol muse Brigid Berlin. Read more about Honey and Brigid Berlin. PORFIRIO RUBIROSA. Though Porfirio Rubirosa's memoirs were never published in book form (and according to Alice-Leone Moats, they were tepid at best), there is an excellent profile of him in Thierry Coudert’s lavish coffee table book, Café Society, Socialities, Patrons, and Artists, 1920-1960. However, Courdert is incorrect on one point: Rubirosa did not marry Zsa Zsa Gabor’s sister Eva when his romance with Zsa Zsa ended. Courdert was perhaps thinking of Zsa Zsa's other sister Magda, who married Zsa Zsa's ex-husband, film director George Stevens. Read more about Thierry Coudert's Café Society. |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed