Ophira Eisenberg

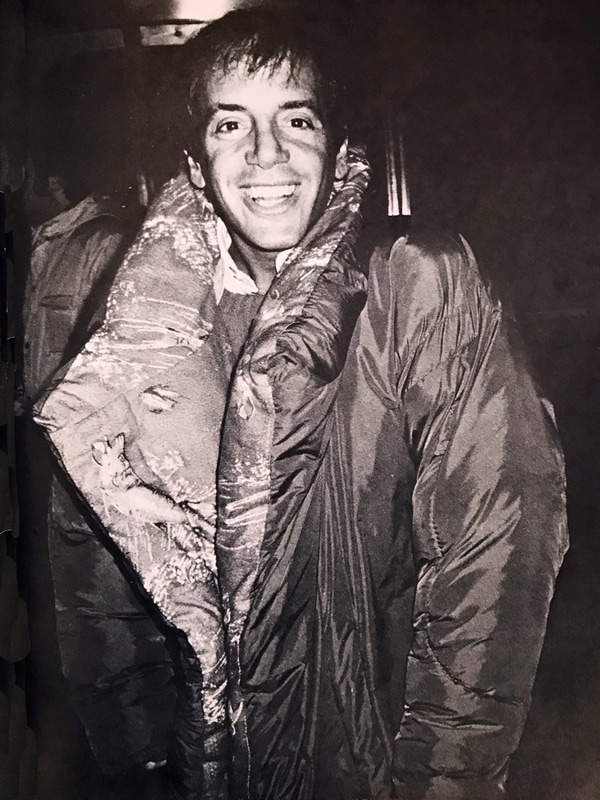

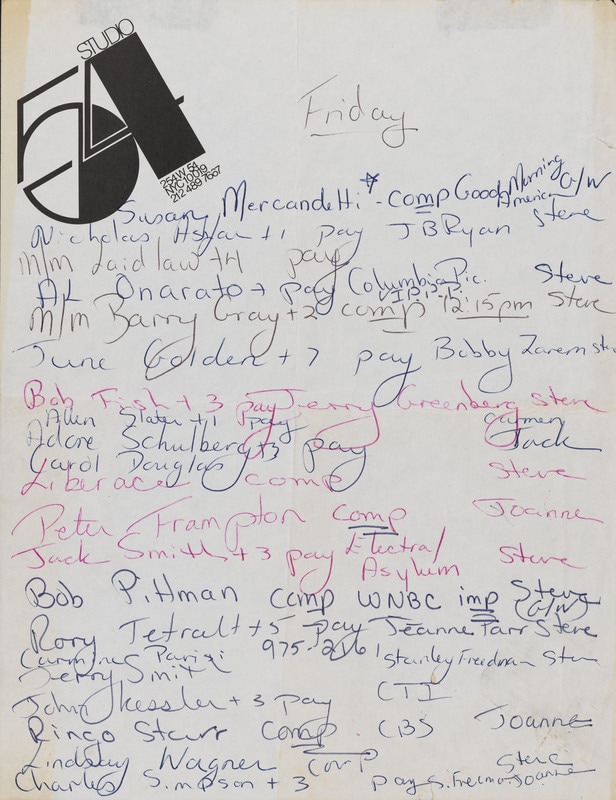

In Wednesday's New York Times, Ian Schrager noted that it was his Studio 54 partner Steve Rubell who coined the phrase “bridge and tunnel.” Rubell used it to describe the wannabes on the wrong side of the Studio 54 velvet rope: those whose heavy gold chains jangled against overly exposed hairy chests and whose suits were one hundred percent polyester. Said Rubell, “We can’t let the bridge-and-tunnel people come in. That’ll kill the night.”

The paradox, of course, it is bridge-and-tunnel to call out others as bridge-and-tunnel. A blue-blood response would be to pretend that no such distinction exists, or in the alternative, to invent a less snobbish euphemism for it.

Schrager told the Times, “The ultimate irony is that [Steve Rubell and I] were bridge-and-tunnel people.” Yet Ian Schrager is a prime example of how this pejorative no longer denotes place of birth. He has become its antithesis. A trait of the bridge-and-tunnel personality is to confuse lavish expenditures of cash with good taste. That does not describe Schrager, America's leading boutique hotelier.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed