Steve Wynn, Investor’s Day Presentation, 2016

“In New York it is chic for people who have money to live in close proximity to people who are poor.”

Stephen Birmingham, Life at the Dakota, 1979

On the surface, at least, it appears as though Steve Wynn does not think so. When he told investors that the rich are only attracted to other rich people, he surely failed to anticipate that it would become national news. Was his opinion just a gaffe, or was it a Marie Antoinette moment that speaks to the zeitgeist of our era? Also, does it even signify how Wynn himself actually behaves or believes?

Escalating property values have made Birmingham’s assertion more difficult to achieve, but its spirit remains true. It continues to be chic for the poor and rich to live in close proximity. Part of the magic of New York City (or any interesting metropolis) is the mix—the eclectic assortment of people willing to brave the challenges of urban living. That mix includes both the “haves” and “have nots.” Of course, some of the creative types that fall into the “have not” category will in time prove to be “have not yets.” That, however, is to be expected. One of the cardinal rules of a mix is that it must be stirred.

Consider New York City’s Studio 54. No club, no matter how celebrity-filled or frequently mentioned in Page Six, has come close to 54’s legendary status. The success of that 1970s-era disco was due not to its homogeneity but to its opposite: the combustible assortment of people it attracted. The club had its fair share of the rich and famous, but as Bob Colacello astutely observed, “It is quite wrong to think of Studio 54 as a place where people went to look at celebrities, it was in a way where celebrities went to look at people.”

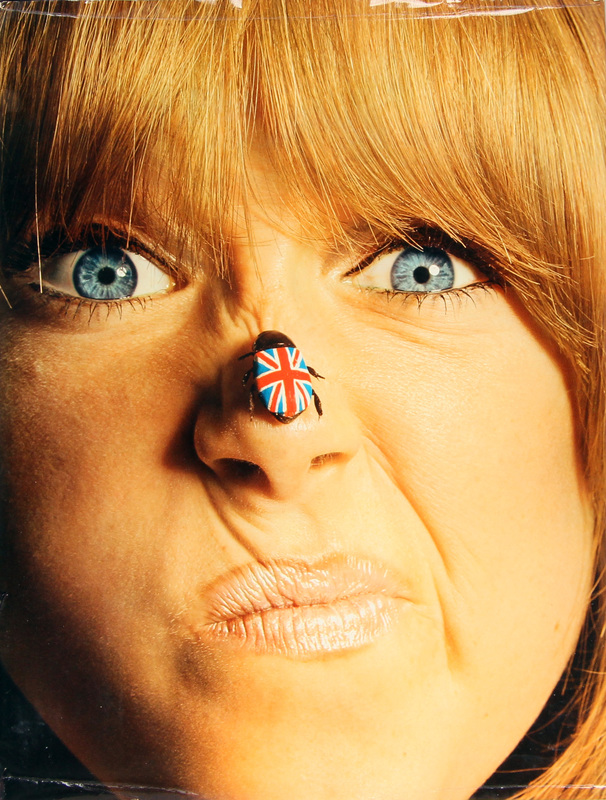

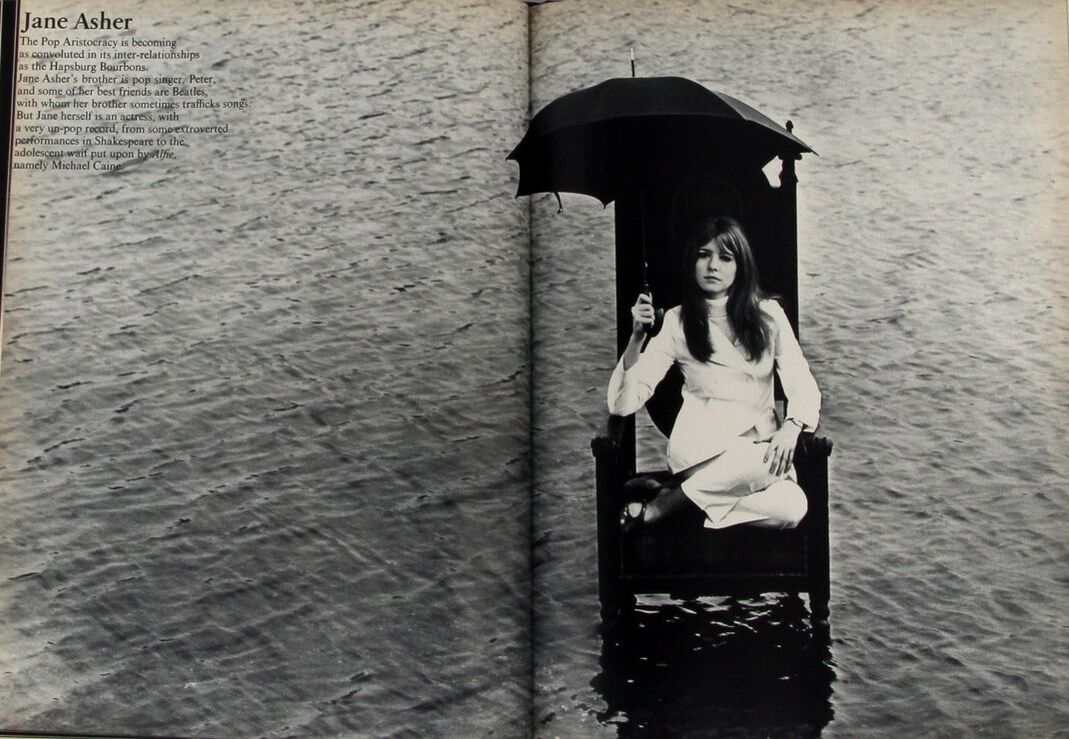

Another exciting place and time was the Swinging London scene of the 1960s and early 1970s. In that era, it was not only fashionable to mix with the poor; it was necessary to do so with a pronounced Cockney accent. The Etonians were not loaded onto tumbrils, but they went undercover until the end of the decade when Margaret Thatcher made them fashionable again.

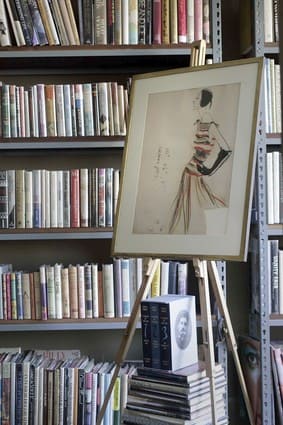

One need not dive that far into the past for examples, however. Bruce Weber and Nan Bush’s annual periodical All-American celebrates those who exemplify the best in style and individuality, with scant attention to income level. Greybull Press, from the early 2000s, also mixed those from a variety of backgrounds and social classes in such books as Height of Fashion, Joseph Szabo: Teenage, and The Book on Vegas (which Steve Wynn has on his shelf, perhaps).

Moreover, before condemning Steve Wynn as a modern-day Marie Antoinette, consider the possibility that like the French queen, his opinions are more nuanced than the mob supposes. In Los Angeles, I once asked my driver what his plans were for the long weekend. He replied that he was chauffeuring Steve Wynn to Las Vegas, as he did most weekends. Wynn was living in Beverly Hills, and because he disliked flying, traveled to Las Vegas by car. He praised Wynn as personable and courteous. Because Wynn would not require transport again until the return drive to Los Angeles, he would give the driver handfuls of free coupons to restaurants and attractions and tell him to go enjoy himself. Such magnanimity suggests Steve Wynn is not quite the out-of-touch snob that his comment to his investors made him appear to be.

The best book on the Studio 54-era is its unofficial high school yearbook, Andy Warhol’s Exposures. Two of the great books on Swinging London are The Birds of Britain and Goodbye Baby & Amen, A Saraband for the Sixties.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed