Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev, The Man and His Era

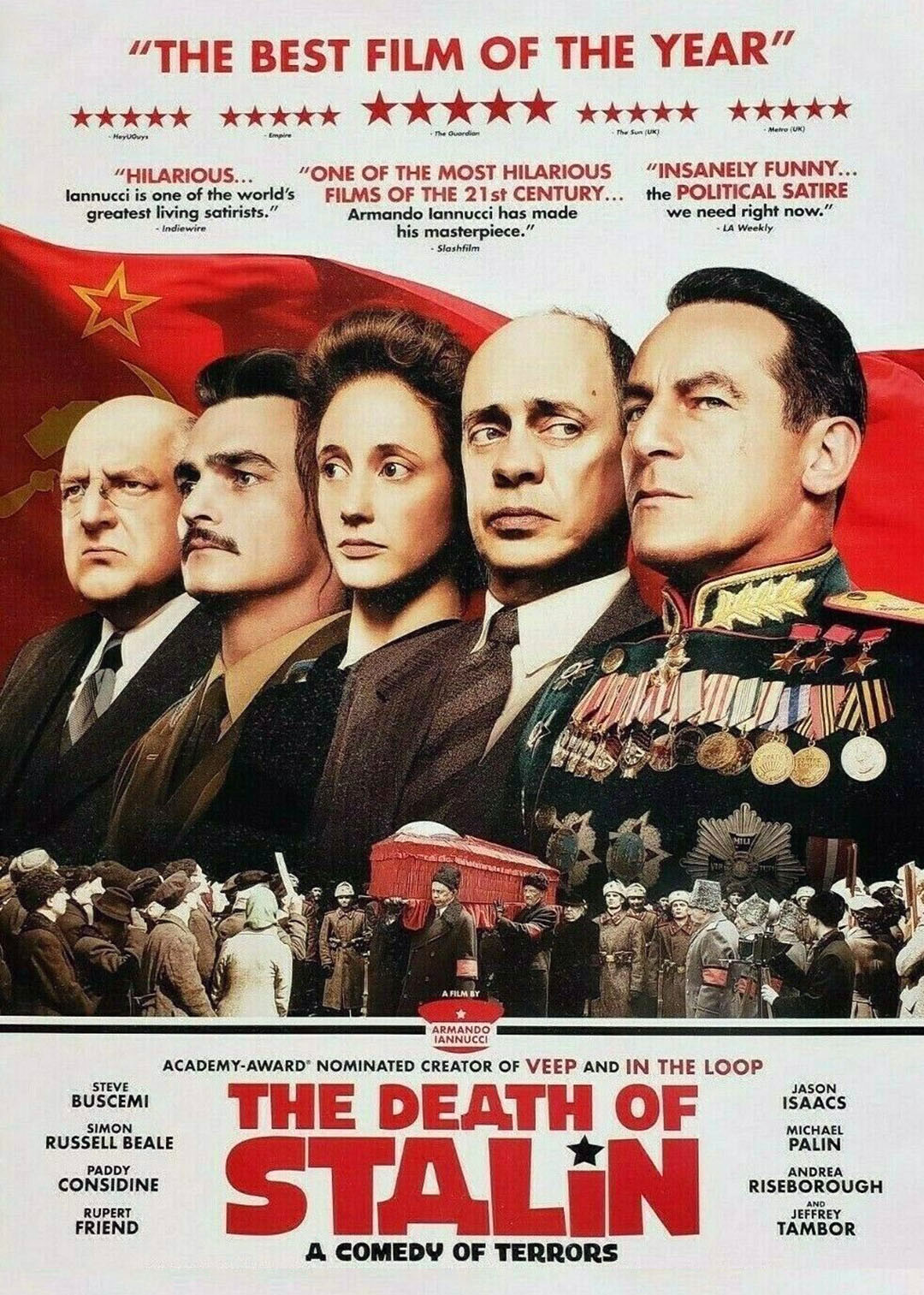

It is impossible to put a positive spin on the bad. Khrushchev was a faithful henchman to brutal Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. It explains his improbable rise from peasant stock to Politburo heavyweight. Working under Stalin was akin to playing Russian Roulette. It was a game of chance that could easily result in death. Had morality gotten in Khrushchev’s way, it would have ended his career and probably his life. Yet, Khrushchev was not simply following orders to survive. Richard Pipes, writing for the New York Times, concluded, “While most of his minions feared and detested Stalin, Khrushchev actually came to admire him. Having become in the 1930's Stalin's pet, he enthusiastically participated in his slaughters.”

Furthermore, Khrushchev’s ruthlessness did not end with Stalin’s death in 1953. In his defense, it couldn’t. There was no definitive line of succession built into the Soviet political structure, and only by manipulation did Khrushchev become leader. His actions were not exactly as they were portrayed in the recent black comedy The Death of Stalin, but nor could they be categorized as nonviolent.

It was after Khrushchev firmly established his hold on power (circa 1956) that he took Kremlin watchers by surprise by publicly denouncing Stalin and reversing the worst atrocities of his regime. Fearing annihilation in an un-winnable nuclear war, Khrushchev also initiated détente with the West. It turned out that he did have a conscience (or somehow acquired one). From the hindsight of the 21st Century, we now understand that Khrushchev's historical significance is more as a precursor to Mikhail Gorbachev than as barbaric protégé to Joseph Stalin.

As part of his détente initiative, Premier Khrushchev embarked on a state visit to the United Kingdom. He was not a worldly man. Knowing only the barbarousness of home, he could did not quite understand the non-violent nature of a Western-style democracy. When Khrushchev’s interpreter fell ill, a mistake in translation illustrated that point quite brilliantly.

The hastily acquired substitute interpreter, whose ruddy complexion suggested he had been drinking, was not up to the task. When avid outdoorsman Lord Tony Lambton was introduced to Khrushchev as being the best shot in England, the interpreter clumsily translated it into Russian as, “Lord Lambton is to be shot tomorrow.” This was absurd. Execution without trial did not happen in 20th Century Great Britain. Yet, Khrushchev, accustomed to life in the Soviet Union, was oblivious. He took it to mean that Lord Lambton "was under sentence of death, and shortly to be executed." Per Lady Diana Mosley (who heard the story directly from Lord Lambton), "Khrushchev thought it quite normal but patted him on the shoulder kindly."

SideBar: Khrushchev and Johnson, A Lesson on Power

Robert Caro, The Passage of Power: The Years of Lyndon Johnson IV

The most historically significant parallel between Khrushchev and Johnson was how both behaved once achieving power. Their actions proved Robert Caro's point: It is a “cliché says that power always corrupts, what is seldom said, but what is equally true, is that power always reveals.”

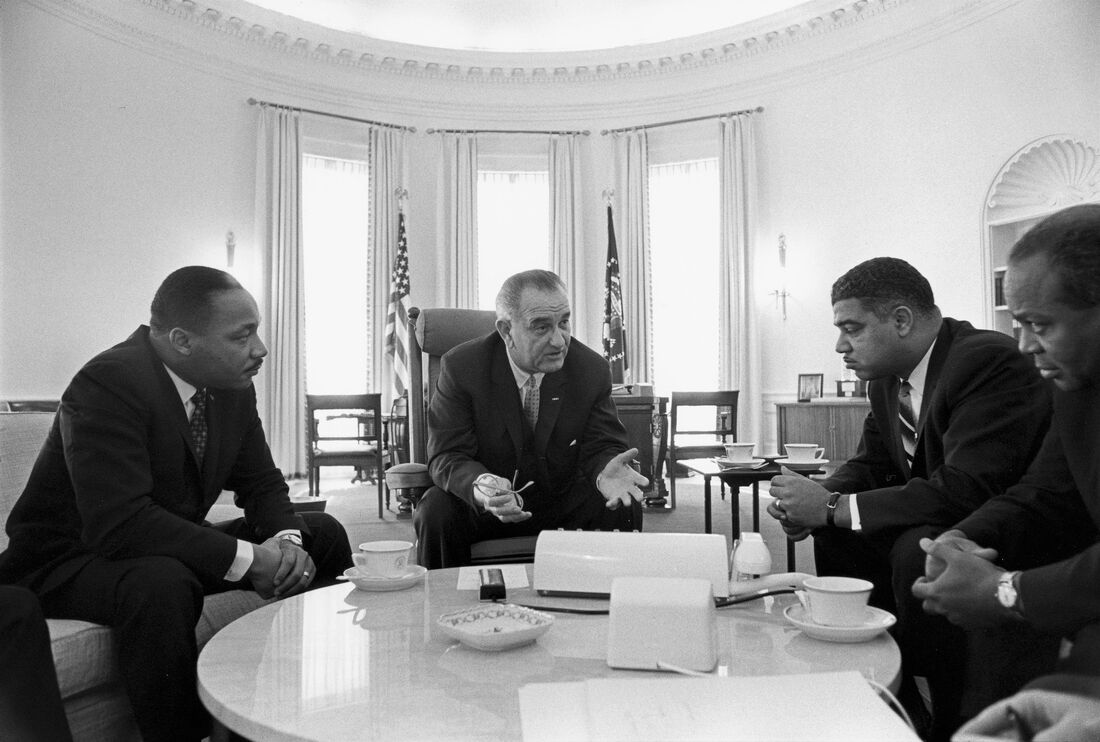

When Khrushchev ascended to the top position, the world expected him to follow Stalin's lead. Instead, he repudiated him. Johnson did one better than his Soviet counterpart by repudiating the Congressional version of himself. From Johnson's first year in Congress in 1937 to 1956, by which time he was Senate majority leader, Johnson worked to defeat civil rights legislation, utilizing the filibuster and procedural devices to thwart a burgeoning pro-civil rights majority. When, in the late 1950s, Johnson began contemplating a run for the presidency, he released his grip just slightly, permitting a toothless civil rights bill to pass.

Flash forward to November 1963. Johnson's compatriots in the South had successfully filibustered the Kennedy administration's proposed civil rights legislation. It was going nowhere. When Kennedy was assassinated, the Southern coalition might have reasonably expected a President Johnson would continue doing for them what he had done so successfully as Senate majority leader. He would discourage, or if necessary, veto civil rights legislation. They were wrong. In fact, he used all of the skills he had learned as Senate majority leader against his former allies. With four votes to spare, President Johnson and Northern Democrats in the Senate defeated the months-long filibuster then being waged by the Southern senators.

Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the very sort of legislation that Johnson had worked so hard to defeat for over a quarter of a century. And, this law had teeth. Per Robert Caro: “It was Abraham Lincoln who ‘struck off the chains of black Americans, but it was Lyndon Johnson who led them into the voting booths, closed democracy’s sacred curtain behind them, placed their hands upon the lever that gave them a hold on their own destiny, made them, at last and forever, a true part of American political life.”

The Big Picture

Note. It is complicated, because unlike a relay race, progress does not consistently move foreword. Consider President Johnson's disastrous escalation of the conflict in Vietnam, which occurred after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed